John Muir Hits the Trail

A Scottish sheepherder, cross-country hiker and Civil War draft dodger, John Muir arrived in Yosemite in 1868. The first white man to explore the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, an avid naturalist and writer, he joined with Century magazine, the Southern Pacific Railroad, and a group of influential Californians to lobby the U.S. Congress unceasingly until, in 1890, they established Federal jurisdiction over greater Yosemite; the valley and the Mariposa Grove remained as state parklands.

Meanwhile, tourism thrived. Camp Curry (now called Half Dome Village) opened to nine guests on July 1, 1899. Stepping off their stagecoaches, exhausted and grimy, the arrivees were greeted by camp staff who whisked away the road dirt with feather dusters. For $2 a day, guests got three meals and a clean napkin, and slept in tents with canvas roofs and wood floors (as we can today). By the summer of the next year, stages and wagons shared the toll roads with a few automobiles.

Teddy and John Muir Go Camping

In the spring of 1903, the intrepid outdoorsman, President Theodore Roosevelt, went camping with John Muir, and together, they rode horses and tramped around Yosemite, got caught in a brief snowstorm, and slept under forty army blankets at Glacier Point, in the Mariposa Grove and near Bridalveil Fall. In the glow of campfires, the president listened to Muir, who warned that Yosemite would be changed forever by sheep grazing, mining and logging. Greatly moved by his experience, Roosevelt exclaimed, “. . . three of the most delightful days in my life!” and he was instrumental in adding the valley and the Mariposa Grove to the National Park in 1906.

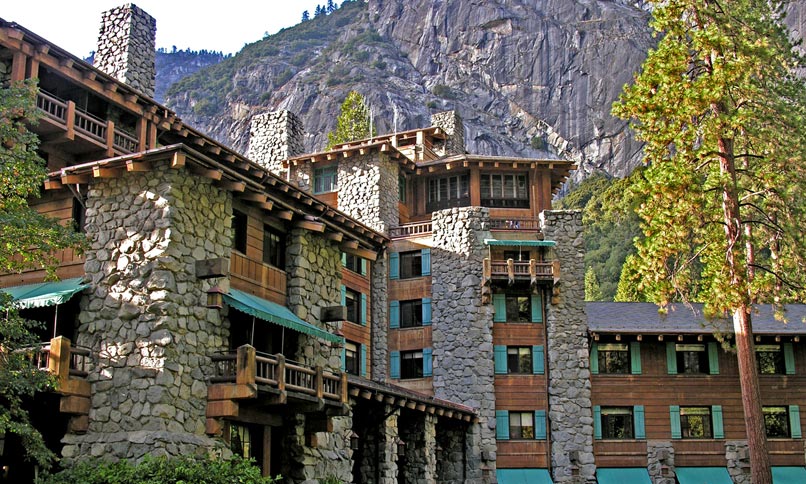

A year later, the Yosemite Valley Railroad was completed, offering passengers a comfortable ride to the western edge of the park. In 1926, a year-round, paved road opened from Merced into the valley, and by 1927, well-heeled tourists could stay at the Ahwahnee Hotel, standing castle-like at the foot of a glacier-carved landmark, the Royal Arches. Today, tall stone fireplaces and soaring, log-beamed ceilings, Native American artifacts and stained-glass windows create the same, impressive, museum-like atmosphere as they did in the Roaring Twenties.

In contrast, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, the U.S. government looked the other way while homeless Americans lived in the valley in their cars and in makeshift shelters, eating fish from the Merced River. A number of trails, stone bridges and buildings were constructed in the ‘30s by the WPA. In 1932, the Victorian-style Wawona Hotel and golf course opened as did the first ski school in California at Badger Pass soon after, outfitted with rope tows and a T-bar.

Opening the rugged high country and spectacular Tuolumne Meadows to public use, and providing a shortcut over the Sierras, the paved Tioga Road opened in 1961, winding through stunning mountain scenery at 9,941 feet––the highest vehicle pass in the state.

21st Century Tourism in the National Park

By the turn of the new millennium, nearly 4 million visitors a year were enjoying the great outdoors of the National Park. Unlike visitors of the 19th and early 20th centuries, who encountered a relatively untouched wilderness in solitude, those of the 21st century bask in the scenic glories of Yosemite from the comfort of their RVs and their automobiles. They tour the valley in open-air tram cars and air-conditioned buses, and watch big-screen TV in the pizza parlor at Half Dome Village. They sleep in snug tent cabins and in hotel and lodge rooms, and they learn of the adventures and the philosophy of John Muir at weekly one-person shows starring Lee Stetson, a long-time Muir impersonator.

Although the granite monoliths, the waterfalls, the spires and the snowcapped peaks remain the same, the true wilderness lies in the Yosemite high country, beyond Tuolumne Meadows, where old Indian trails wander into the mountains and down the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, where John Muir wrote, “In wilderness lies the hope of the world––the great, fresh, unblighted, unredeemed wilderness.”

Majestic Yosemite Hotel Tour

A masterpiece of Art Deco and California Craftsman architecture, the monumental Majestic Yosemite Hotel (formerly the Ahwahnee Hotel) opened in 1927 and instantly became one of the icons of Yosemite Valley. Priceless Native American baskets and artifacts, historic photos and artworks, and Persian and American Indian rugs create a museum-like atmosphere. The landscaping was originally designed by the legendary landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr.

With a 34-foot high ceiling and baronial chandeliers, the 130-foot-long dining room is impressive, with massive sugar pine log beams and views of the woods and cliffsides through the sky-high windows. Every Christmas season, the dining room is elaborately decorated and glowing with candles and merriment when the old-English-style Bracebridge Dinners are held. “Christmas Dinner at Bracebridge Hall,” a story by American author, Washington Irving, recounts the lively, colorful holiday parties of an English squire of the 18th century. Each year since 1927, the music, the lavish feast and even the dress, are recreated in a series of evenings so popular that people often wait for years to get on the reservation list.

Register in advance for the free, 1-hour guided tour of the hotel by an historian who describes the architecture, art, famous guests and the historic role of the hotel. The kids can listen to evening fireside storytelling in the Great Room, too.

Wandering the Majestic on your own: The Great Room is the immense gallery and lounge where 3-story-tall stained-glass windows, a walk-in fireplace and chandeliers as big as Volkswagens create a castle-like atmosphere. Notice the large vintage photos of cowboys and Indians. The cowboy is Jim Helm, who in the late 1890s was in charge of the stables located where the Majestic now stands. The Native American man is Chief Leemee in a photo taken in mid-twentieth century. Taken in 1899, the photo of mother and child shows Yosemite Falls and a traditional packboard used for babies. The same photographer, Ralph Anderson, took the photo of the Yosemite Indian making a basket and grinding corn. Another image, taken in the late 1800s, is Chief Francisco Jeorgley, with a deerskin around his waist and carrying a bow and arrow.

Behind the Great Room discover quiet, snug rooms, each more charming than the next.

The Solarium: crystalline light streams in through the windows, framing views of Yosemite Falls and pristine meadows and conifers, in a setting so idyllic that weddings are held here. Notice the wrought iron, Art Deco-era floor lamps with parchment shades.

The Winter Club Room: recalling halcyon days of skiing and sledding in the 1930s and ‘40s are old photos around the room, along with antique skis and snowshoes.The Mural Room: comfy seating in front of a high window with a view of Upper Yosemite Fall, a brass-domed fireplace and a wall-length, William Morris-style painting depicting local flora and fauna.

The Great Room Outer Lobby: a small museum and gathering place, with old books on the mantel above a huge fireplace, and a display of priceless Paiute baskets.

This is Part Two of Yosemite History and Tours.

For Part One, click here.

Yosemite History and Tours

Springtime in Yosemite National Park: Wildflowers and Waterfalls!

1 Comment

Beautiful photos and inspirational history and descriptions of special places. Each time I visit Yosemite, I love it more. This article reminds me that it has been way too long since I last spent time at this holy place.